This analysis was based on a challenge from the Codecademy Data Science skill path which involves looking at a huge bank of questions from the US game show, Jeopardy! It is a dataset that has probably been widely analysed, and like ‘Titanic Surivival’ and ‘Predicting House Prices’, it will have been seen plenty of times before. Nonetheless, I think it is interesting, and I found working on the challenge instructive.

One of the given tasks is to create a function that will filter the questions based on specified terms. I created a ‘hard’ and a ‘soft’ version of this function – the former filters the questions so that they contain all the words in the given list of specified terms, the latter will return questions if they contain any of the terms in the list. This was achieved using the ‘all()’ and ‘any()’ methods respectively.

We’ll start off by importing pandas and loading up the dataset. I will use pyplot later to create some visualizations.

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

pd.set_option(‘display.max_colwidth’, None)

df = pd.read_csv(“jeopardy.csv”)

df.describe()

Next, the function definitions. We will call .lower() on ‘question’ and ‘word’ so that the comparison is case-insensitive. When checking a word, we add a space to the beginning and end to make sure that it is the actual word that is matched, and not a matching substring for another word. Without this, for example, the word ‘king’ might get unintentionally matched to any questions that included the word ‘viking’.

def hard_filter_questions(df,word_list):

filter = lambda question : True if all(” ” + word.lower() + ” ” in question.lower() for word in word_list) else False

hard_filtered_df = df[df[‘Question’].apply(filter)]

return hard_filtered_df

def soft_filter_questions(df,word_list):

filter = lambda question : True if any(” ” + word.lower() + ” ” in question.lower() for word in word_list) else False

soft_filtered_df = df[df[‘Question’].apply(filter)]

return soft_filtered_df

word_list = [‘King’, ‘England’]

hard_filtered_df = hard_filter_questions(df,word_list)

soft_filtered_df = soft_filter_questions(df,word_list)

print(len(hard_filtered_df))

print(len(soft_filtered_df))

51 2313

So we can already see there is a big difference in result depending on how we filter the dataset. Using the more stringent criteria results in a much narrower set of data, as you would expect. It goes to say as well, that if you only wanted to filter on one term, then it does not make a difference which version of the function you use. You could write a broader function, ‘filter_questions’, that takes an additional argument in the form of a Boolean value that will determine if a hard or a soft filter is performed. For example, if ‘hard_filter == True’ then run the comparison block that uses all(), else use the block that uses any(). The advantage of having the two seperate function definitions is that it is perhaps a bit clearer when looking at the code when a hard filter has been performed instead of a soft one.

Next up, we wanted to perform some aggregate analysis on the ‘Values’ column. This contains the prize money value amount of each question, which supposedly is a measure of a question’s difficulty (as reward should be proportional to difficulty). In order to do this we first had to clean up the values. In their original form, they are represented as strings, with dollar values preceding the monetary values and comma delimiters for the larger values. These all need to be removed before we can convert to float. Again we use a lambda function with apply() on the target column.

clean_value = lambda value : float(value.replace('$','').replace(',','')) if value != 'no value' else 0

df['FloatValue'] = df['Value'].apply(clean_value)

Now let’s compare the difficulty of questions about kings with questions about queens:

king = ['King']

king_df = hard_filter_questions(df,king)

queen = ['Queen']

queen_df = hard_filter_questions(df,queen)

king_average_value = king_df.FloatValue.mean()

queen_average_value = queen_df.FloatValue.mean()

print(round(king_average_value,2))

print(round(queen_average_value,2))

806.97

767.5

So, on average, we think that King questions are a bit more difficult.

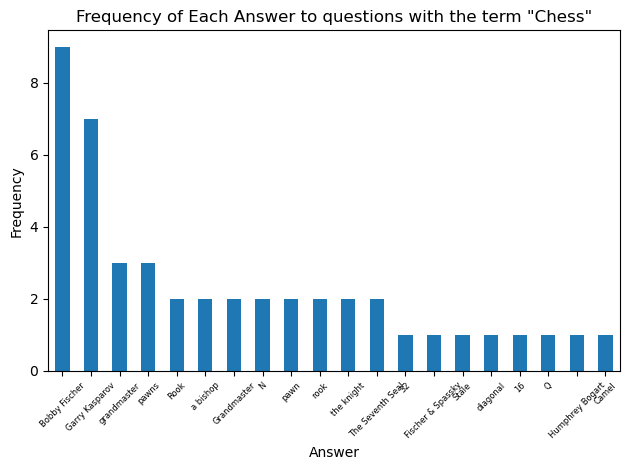

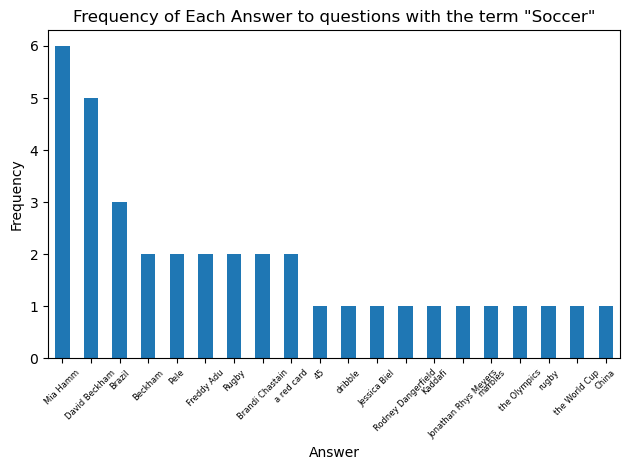

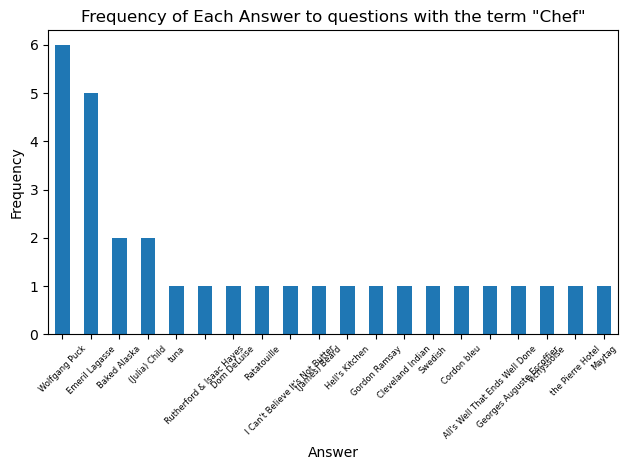

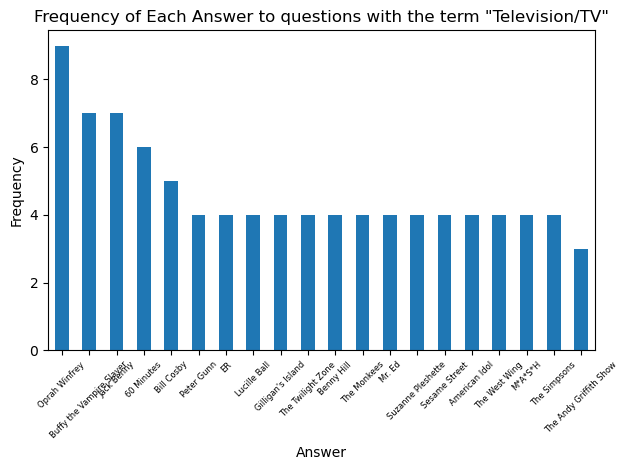

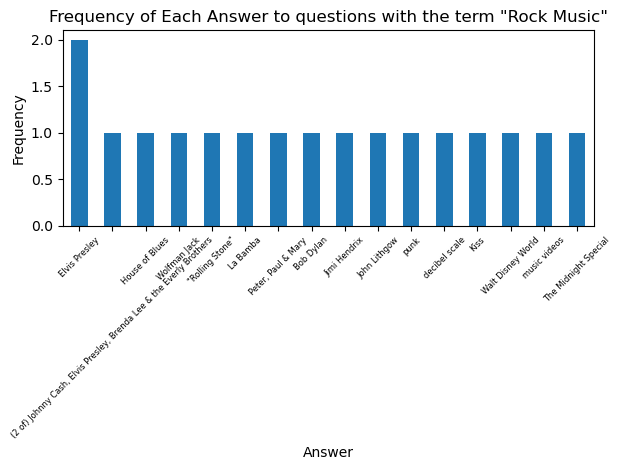

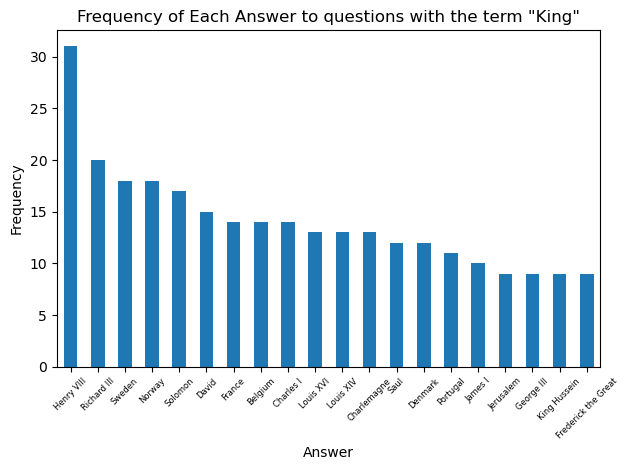

The next task is to find the number of unique answers to questions inside a filtered dataset. Going back to the kings example, when asked questions about kings on the game show, are there certain answers that come up more often than others?

The value_counts() method provides a perfect solution here. We can just define our ‘counts’ of unique answers to a filtered question bank as the value_counts() of the Answer column. I wrote two seperate functions that utilize the counts item. One of them simply prints a frequency count of each unique answer, the other one plots the frequency of answers as a bar chart (restricted to the 20 most frequent to keep the chart tidy)

def get_unique_answers(filtered_df):

counts = filtered_df['Answer'].value_counts()

return counts

def display_unique_answer_counts(counts):

for answer, count in counts.items():

print(f"{answer} : {count}")

def plot_unique_answer_counts(counts,term):

# plots the frequencies of the top 20 most common answers

counts.head(20).plot(kind='bar')

plt.xlabel('Answer')

plt.ylabel('Frequency')

plt.title(f'Frequency of Each Answer to questions with the term \"{term}\"')

plt.xticks(rotation=45, fontsize = 6) # Rotate labels 45 degrees and set the font-size so the labels don't overlap

plt.tight_layout() # Adjust layout so labels don’t get cut off

plt.show()

king_df = hard_filter_questions(df, ['King'])

#display_unique_answer_counts(get_unique_answers(king_df))

plot_unique_answer_counts(get_unique_answers(king_df), 'King')

So Henry VIII takes the prize as the king who is the solution to the greatest number of Jeopardy! questions. Let’s look at the most common answers for some other categories: